South Carolina and the United States currently finds itself in a profound and damaging crisis of contradiction regarding cannabis governance. Despite a nationwide embrace of cannabis—ranging from medical treatments to recreational enjoyment—the federal government maintains an outdated legal framework that actively undermines state autonomy, public health initiatives, and principles of social justice.1

This systemic conflict stems from the federal classification of cannabis. Under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970, cannabis and its derivatives remain Schedule I substances, a classification reserved for drugs deemed to have the “highest potential for misuse” and “no acceptable medical use”.2 This status has remained static for over 50 years, even though a majority of states have established laws allowing for the cultivation, sale, distribution, and possession of cannabis or low-THC products.3

The decades-long prohibition did not even achieve its stated goal: market control. Government-funded researchers found that high school seniors consistently reported that marijuana was “fairly easy” or “very easy” to obtain, with 80% to 90% reporting easy access between 1975 and 2012.4 The primary observable effect of this policy was punitive enforcement directed at specific populations, culminating in more than 17 million marijuana arrests since 1995. In 2022 alone, one person was arrested for a marijuana offense every two minutes, with more than 90% of these arrests being for simple possession, not manufacture or distribution.4

Since availability remained consistently easy despite aggressive enforcement, the policy’s true function shifted away from market control and toward mechanisms of social control and criminalization. Comprehensive cannabis reform must therefore move beyond simple legalization to prioritize systemic redress for the racially biased enforcement of the past century, requiring dual action in legislative modernization and dedicated restorative justice initiatives.

A Century of Fear: The Architecture of Hysteria

The foundation of federal cannabis prohibition was not built upon scientific evidence or public health concerns, but rather on a deliberate campaign rooted in xenophobia, economic protectionism, and sensationalism.

Drug laws were selectively deployed to target specific communities long before the modern “War on Drugs” was officially declared. In the 1910s and 1920s, anti-cannabis laws were introduced throughout the Midwest and Southwest, explicitly targeting Mexican Americans and migrants.5 This established an early, insidious precedent where drug legislation functioned as an instrument of social control, enabling the legal harassment of groups deemed “deviant or disliked” by the dominant social organism.6

The federal crusade was orchestrated by Harry J. Anslinger, the first Commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), who held his post for an unprecedented 32 years until 1962 . Anslinger spearheaded the movement to transform cannabis from a nebulous social ill into a political and social threat.7 His prohibition strategy was explicitly racial, asserting that Black people and Latinos were the primary users of marijuana and claiming that the substance caused them to “forget their place in the fabric of American society” . This racially charged propaganda was extended to cultural figures, notably jazz musicians, whom Anslinger accused of creating “Satanic” music under the drug’s influence, leading to the notorious persecution of singer Billie Holiday .

To generate public and political support, Anslinger relied on sensationalized, non-scientific claims, documented in what was referred to as his “Gore File” . This tawdry collection consisted of lurid, race-tinged stories of crimes and sex acts, mostly taken from exaggerated articles in Hearst-owned newspapers, rather than producing any evidence of a true crisis related to marijuana use.6 Propaganda films of the era, such as Reefer Madness, further solidified the false perception of cannabis as a dangerous substance leading to violence and depravity, thereby exploiting and confirming existing racial biases .

This campaign culminated in the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which formally set the stage for decades of prohibition by implementing a taxing scheme that effectively outlawed cannabis.7 While Anslinger’s prejudice provided the moral panic, powerful economic interests played a definitive role. Newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who strongly promoted anti-marijuana hysteria through his publications, was believed to have an interest in protecting his investments in the wood-pulp industry. Hemp, which produces superior fiber from the cannabis plant, posed an economic threat to wood-pulp.9 By taxing cannabis cultivation and sale out of existence, the 1937 Act rendered industrial hemp—a fiber source completely unrelated to narcotics production—almost worthless.9

|

Era |

Key Legislation/Event |

Primary Driver |

Immediate Consequence |

|

Early 20th Century |

Local Anti-Cannabis Ordinances |

Xenophobia targeting Mexican and Chinese immigrants.5 |

Foundation of state-level criminalization. |

|

1937 |

Marihuana Tax Act |

Racial prejudice (Anslinger) and economic protection (Hearst/wood-pulp).14 |

Institutionalized federal control; collapse of the U.S. hemp industry.9 |

|

1970 |

Controlled Substances Act (CSA) |

Political strategy (Nixon/Ehrlichman) targeting political dissidents and minorities.5 |

Classification as Schedule I, cementing the conflict between law and science.2 |

|

1996 – Present |

State Medical/Recreational Legalization |

Public health advocacy and democratic mandate.15 |

Created the modern federal/state conflict and drove social equity movements. |

Fifty Years of Institutionalized Harm

The prejudicial framework established in the 1930s was formally institutionalized during the Nixon administration. The passage of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in 1970 imposed a unified legal framework at the federal level, classifying marijuana as a Schedule I controlled substance and cementing its illegal status.3

The official declaration of the War on Drugs by President Nixon in June 1971 cemented an era of aggressive drug enforcement.5 The underlying motivations were revealed years later when a top Nixon aide admitted that the strategy was explicitly designed to target “Black people and hippies” as a means of disrupting political opposition groups.5 This explicitly political and racially targeted intent laid the groundwork for dramatically uneven enforcement of drug laws, a pattern maintained by disproportionate police presence, searches, and arrests in communities of color.17

Quantifying the Disparity

Despite the fact that rates of cannabis use are statistically similar across racial lines, Black and brown people are disproportionately impacted by drug enforcement and sentencing practices.5

Police make approximately 550,000 arrests for cannabis offenses each year, and over 90% of these arrests are for simple possession.5

Across the 50 states, Black people are, on average, 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana charges than white people . This persistent disparity reflects increased racial profiling by law enforcement .

The disproportionate enforcement feeds the carceral state; two-thirds of all people incarcerated in state prisons for drug offenses are people of color.20

|

Metric |

Data Insight |

Broader Implication |

Source |

|

Arrest Likelihood (Black vs. White) |

Black people are 3.6x more likely to be arrested for marijuana charges nationally. |

Enforcement is based on racial profiling and concentrated policing, not usage rates. |

18 |

|

Arrest Type |

92% of cannabis arrests are for simple possession. |

Prohibition focuses heavily on criminalizing individual users rather than trafficking/distribution. |

20 |

|

Socio-Economic Harm |

Criminal records lead to labor market penalties, denial of housing, and loss of public benefits. |

Enforcement exacerbates long-run racial and economic inequality. |

5 |

|

Incarceration Rate |

Two-thirds of all people in state prisons for drug offenses are people of color. |

The policy fulfills its initial political design of targeting specific demographic groups. |

5 |

The collateral damage extends far beyond incarceration. The possession of a criminal record, often stemming from a low-level cannabis offense, generates substantial labor market penalties, severely limiting employment and earnings potential.19 These penalties, known as collateral sanctions, affect virtually every aspect of a person’s civil life: denial of food stamps, loss of public assistance, suspension of driver’s licenses, and forfeiture of voting rights.5 Since arrests disproportionately target communities of color, this enforcement operates as a continuous, generational tax on these communities, perpetuating poverty and inequality.19

Furthermore, the dramatically uneven enforcement has exacted a sociological toll, specifically eroding trust in law enforcement within minoritized communities.17 The constant threat of disproportionate police presence breaks down “collective efficacy and social cohesion,” undermining social stability and impacting public health outcomes.24

The Federal-State Impasse and the Call for Reform

Despite federal rigidity, the democratic mandate for reform is clear. Support for legalization surged to 50% in 2011 and reached 64% in 2017—the first time a majority of Republicans also supported legalization.9 This democratic shift fueled state action, beginning with California’s legalization of medical cannabis in 1996 9, followed by Colorado and Washington legalizing recreational use in 2012.9 The progression continues, demonstrated by Vermont legalizing adult use in 2018 and Illinois passing the Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act in 2019.20

Yet, the proliferation of state cannabis laws has created a complex “conflict of laws” with the enduring federal prohibition.1 This divergence paralyzes businesses and creates market confusion.25 Since banks and credit unions are federally regulated, they face existential risk if they conduct business with state-legal cannabis entities, forcing many to operate on a cash-only basis and creating security risks.1 Furthermore, the interstate movement of cannabis, even between two legal states, is barred by federal law.1

This structural contradiction highlights a fundamental flaw: the federal government is effectively crippling state industries through banking limitations and regulatory uncertainty while maintaining the power to intervene selectively via Schedule I status. The current Department of Justice (DOJ) appropriations rider provides only limited protection, barring action against states enforcing medical laws but offering no such safeguard for recreational activities.22 This regulatory abandonment hinders the legal industry’s maturity and inadvertently favors the continued existence of the illicit market.

A Positive Path Forward: Restorative Justice and the Southern Hemp Model

The essential requirement of cannabis reform is the restoration of justice—a dedicated effort to repair the harms inflicted and to ensure that the wealth generated by the new legal industry benefits those previously penalized. The philosophical model guiding this policy must be restorative justice, which focuses on healing, systemic redress, and rehabilitation, rather than retribution.6

The Blueprint for Systemic Redress:

Reparative Action through Record Relief: Record relief must move toward automatic expungement for low-level cannabis convictions.27 Petition-based systems are often inaccessible due to the complexity, time, and cost of legal work required.27 Automatic expungement is the most effective method for universal record clearance, immediately removing the systemic barriers that restrict employment, housing, and educational opportunities for those disproportionately harmed by prohibition.19 Presidential and gubernatorial pardon power also represents a vital executive tool to advance comprehensive restorative justice goals.27

Establishing Social Equity Frameworks: Social Equity programs are paramount for ensuring proportional representation and wealth creation in the new legal industry.29 Successful models, like Colorado’s Social Equity Licensee criteria and New York’s Cannabis Hub & Incubator Program (CHIP), prioritize individuals impacted by prior convictions or high-enforcement area residency, offering critical assistance in licensing, compliance, and securing funding.29 Record relief must be universal and decoupled from market participation to truly address the systemic economic harm caused to all individuals who faced criminalization.

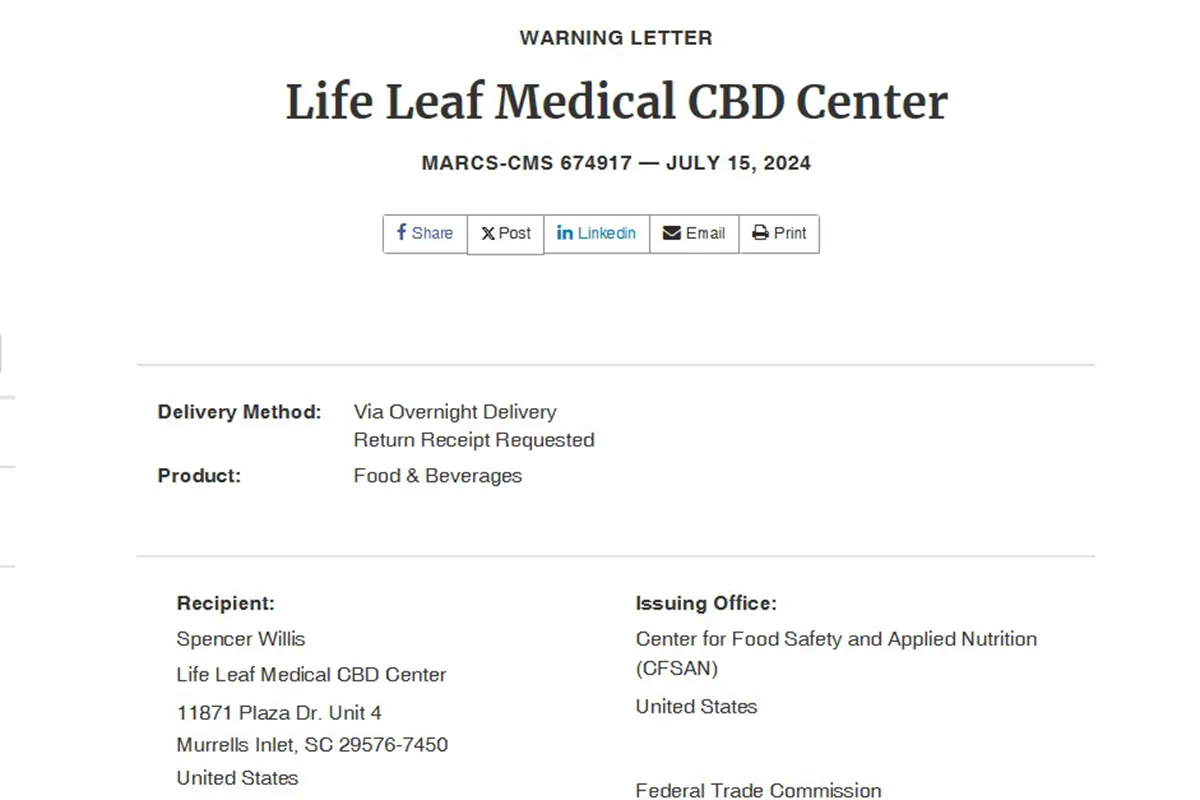

Community Reinvestment and Public Health Governance: Dedicated cannabis tax revenues must be channeled directly back into the communities that bore the brunt of enforcement, funding social services, housing assistance, educational scholarships, and job training.21 Furthermore, the regulatory focus must shift entirely from criminal punishment to public health management.10 This means establishing and enforcing clear, uniform standards for packaging, labeling, and product potency to protect consumers and ensure product integrity.14 The need for robust oversight is evidenced by recent FDA warnings issued to businesses regarding non-compliant products, such as the warning letters sent to South Carolina businesses like Life Leaf Medical CBD Center.13

Charting the Future: Hemp-Based Cannabis in South Carolina

South Carolina stands at a critical juncture, providing a potential template for southern states on how to transition thoughtfully from prohibition to a regulated, equitable market. The state’s immediate path forward should be guided by its most stable asset: the regulated hemp-based cannabis industry.

Organizations like South Carolina Better Wellness Alternatives (SCBWA) are vital, dedicating their efforts to building trust and legitimacy by advocating for “sensible, balanced industry best practices and legislation that prioritizes public health and safety”.13 Their advocacy includes helping consumers navigate the existing “patchwork of regulations that confuse the market”.13 The legislative momentum behind SCBWA’s comprehensive “Blueprint for Progress” 16 charts a positive course:

Compassionate Care and Judicial Modernization: Pending South Carolina legislative efforts include the S0053 bill, which establishes the “South Carolina Compassionate Care Act” to create a comprehensive medical cannabis program.23 Simultaneously, the H3804 bill proposes to decriminalize possession of twenty-eight grams (one ounce) or less of marijuana or ten grams or less of hashish, allowing law enforcement to issue a civil citation instead of a criminal charge.11 This dual approach demonstrates a bipartisan recognition of the need for both patient access and judicial modernization.

Hemp-Driven Economic Growth: The state must leverage its regulated hemp industry, which already provides low-THC products, to supply a safe and consistent market for any future medical program.13 By prioritizing the SCBWA’s Blueprint for Progress—which focuses on stringent industry standards—South Carolina can establish a reputation for quality and safety. This is crucial for protecting consumers from dangerous, unregulated products, as evidenced by the need to issue alerts regarding FDA warnings to businesses concerning non-compliant products.13 A responsible, state-regulated, hemp-based medical program provides an immediate, low-risk path to economic development and patient relief while also building the infrastructure necessary for any future expansion.

By focusing on record expungement (restorative justice), implementing consumer protection standards (public health governance), and leveraging the existing economic foundation of the regulated hemp market (economic equity), South Carolina can successfully dismantle the legacy of fear and build a truly safe, responsible, and equitable cannabis future.

Works cited

A Cannabis Conflict of Law: Federal vs. State Law – American Bar Association, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/resources/business-law-today/2022-april/a-cannabis-conflict-of-law-federal-vs-state-law/

About Cannabis Policy | APIS, accessed November 13, 2025, https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/about/about-cannabis-policy

The Evolution of Marijuana as a Controlled Substance and the Federal-State Policy Gap, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44782

Marijuana Prohibition Facts, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.mpp.org/issues/legalization/marijuana-prohibition-facts/

Fifty Years Ago Today, President Nixon Declared the War on Drugs | Vera Institute, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.vera.org/news/fifty-years-ago-today-president-nixon-declared-the-war-on-drugs

RACIAL MYTHS OF THE CANNABIS WAR – Boston University, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2021/07/FISHER.pdf

THE COMPLICATED LEGACY OF HARRY ANSLINGER – CASE, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.case.org/system/files/media/file/Penn%20Stater%20Harry%20Anslinger.pdf

Social and Economic Equity – Office of Cannabis Management – NY.gov, accessed November 13, 2025, https://cannabis.ny.gov/social-and-economic-equity

Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 | Research Starters – EBSCO, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/law/marijuana-tax-act-1937

CHAPTER 2. A HISTORY OF DRUG AND ALCOHOL ABUSE IN AMERICA Written by: Tammy L. Anderson To appear in, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www1.udel.edu/soc-bak/tammya/pdf/crju369_history.pdf

2025-2026 Bill 3804: Marijuana Decriminalization – South Carolina Legislature Online, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.scstatehouse.gov/sess126_2025-2026/bills/3804.htm

Report Cannabis Overview – National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/cannabis-overview

South Carolina Better Wellness Alternatives: Home Page, accessed November 13, 2025, https://scbetterwellness.org

The man behind the marijuana ban for all the wrong reasons – CBS News, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/harry-anslinger-the-man-behind-the-marijuana-ban/

Timeline of cannabis laws in the United States – Wikipedia, accessed November 13, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_cannabis_laws_in_the_United_States

News & Laws – South Carolina Better Wellness Alternatives, accessed November 13, 2025, https://scbetterwellness.org/news-and-laws/

Race and the War on Drugs – NACDL, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.nacdl.org/Content/Race-and-the-War-on-Drugs

Retroactive Legality: Marijuana Convictions and Restorative Justice in an Era of Criminal Justice Reform – Scholarly Commons, accessed November 13, 2025, https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=7671&context=jclc

Do Recreational Marijuana Laws Reduce Racial Disparities? Evidence from Criminal Arrests, Psychological Health, and Mortality – Moritz College of Law – The Ohio State University, accessed November 13, 2025, https://moritzlaw.osu.edu/sites/default/files/2023-08/DEPC%20Grant%20Result_Sabia_August2023.pdf

Cannabis and Racial Justice – Marijuana Policy Project, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.mpp.org/issues/criminal-justice/cannabis-and-racial-justice/

A Public Health Approach to Regulating Commercially Legalized Cannabis, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2021/01/13/a-public-health-approach-to-regulating-commercially-legalized-cannabis

The Federal Status of Marijuana and the Policy Gap with States | Congress.gov, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12270

Take Action on Cannabis Legislation in South Carolina | SouthCarolinaStateCannabis.org, accessed November 13, 2025, https://southcarolinastatecannabis.org/take-action

How Cannabis Policy Influences Social and Health Equity – NCBI – NIH, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK609489/

Largest Racial Disparities in Marijuana Possession Arrests Across the U.S., accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.criminalattorneycincinnati.com/the-largest-racial-disparities-in-marijuana-possession-arrests-across-the-u-s/

Overview of Cannabis Policy – NCBI – NIH, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK609471/

Reefer Madness: Exploring the Cannabis Hysteria of the 1930s – Linwood House, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.linwoodhouse.co.uk/blog/society/reefer-madness-exploring-the-cannabis-hysteria-of-the-1930s/

Reversing the War on Drugs: A five-point plan – Brookings Institution, accessed November 13, 2025, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/reversing-the-war-on-drugs-a-five-point-plan/

Social Equity – Marijuana Enforcement Division, accessed November 13, 2025, https://med.colorado.gov/social-equity